In the beginning, it was almost possible to believe Donald Trump had a coherent worldview. There were those, like Walter Russell Mead in Foreign Affairs, who argued that the president had a purposeful, Andrew Jackson-inspired “America First” policy. Alliances and treaties, especially trade deals, would be measured according to a narrow definition of national interest rather than long-term global stability. This was a simplistic, nearsighted strategy, but at least it made some political sense. It was what his constituency wanted. The primacy of domestic electoral considerations has certainly been notable in Trump’s world. His withdrawal from the nonbinding Paris climate accord is a lot more popular in places he won, like southern Ohio and western Pennsylvania (with the exception of Pittsburgh), than it is in California, where there are more people working in solar energy than there are coal miners left in the entire nation.

But there is more—or, perhaps more accurately, less—to Trump’s foreign policy than that. There have been at least two other complicating factors. There is the suspicion that aspects of Trump’s global actions, especially his curious relationship with Russia, are tangled up with his personal business interests, including his debts. And, of course, there is the mix of ignorance, personal pique, toxic narcissism, and conspiracy theory that is the hallmark of Trumpery, both foreign and domestic.

In diplomacy, the less said the better. This is not a hard and fast rule. Sometimes a bold statement of principle—“Tear down this wall!”—can be cathartic, but, for the most part, the world today is too subtle for sweeping Presidential Doctrines and red lines, the cancellation of treaties (without fierce provocation), and peremptory tweets. Diplomacy is a language of winks and clauses, of doors left partially open, of balm rather than bombast. Bluster may have its uses in a real estate deal or on reality TV, but it tends to close doors and produce casualties overseas. A nuanced knowledge of an adversary’s culture and history is a distinct advantage. The ability to flirt and flatter is another. Former Secretary of State Warren Christopher once said that a strong bladder was essential for his dealings with the Syrian dictator Hafez al-Assad. Indeed, patience is the cardinal diplomatic virtue. None of these are Trumpian traits—though his judicious use of military power in Syria and Afghanistan offers some hope that he will listen to his military advisers when it comes to the more terrible options available to a president.

It’s too soon to say that Trump is a complete disaster, but he has been a comprehensive embarrassment abroad. He’s alienated friends and comforted adversaries. He’s been crude and foolishly pugilistic—picking a fight with the mayor of London, who is Muslim, after the recent terror attack; picking fights with friendly leaders from Australia to Germany; shoving the Montenegrin prime minister aside at a NATO summit. He’s chosen an able team of advisers—James Mattis at Defense, Rex Tillerson at State, H. McMaster at the National Security Council, and Nikki Haley at the United Nations—but disregards them wantonly. Susan Glasser pointed out in Politico recently that his foreign policy team was taken by surprise when, in an address to NATO’s leaders in Brussels, Trump pointedly didn’t endorse Article 5 of the alliance’s treaty, the guarantee of mutual assistance if any of the allies are attacked. This is the provision that brought the Europeans into the war in Afghanistan after the Sept. And while some of the allies made laughably inept contributions to that war effort, others spent considerable blood and treasure on an operation that became strategically questionable after al-Qaeda was driven from the country and Osama bin Laden killed. It would take two weeks of controversy for Trump to say publicly that he affirmed Article 5.

Trump’s presidential campaign, tawdry as it was, reflected a legitimate American uneasiness with the global status quo. The diplomatic architecture and financial assumptions that have been in place since the end of World War II have corroded; domestically, there needs to be a more intense focus on how to maintain a middle class in an age of globalization and robotics. At his best, Trump promised a new look at these issues. He could be refreshingly candid about past failures: the war in Iraq, for example. His insistence that our NATO allies take more aggressive action to defend themselves, especially against the terrorist threat, was a valuable carryover from the Obama and Bush administrations; his willingness to get rowdy about it may have been a rare case of candor being a diplomatic asset rather than a liability.

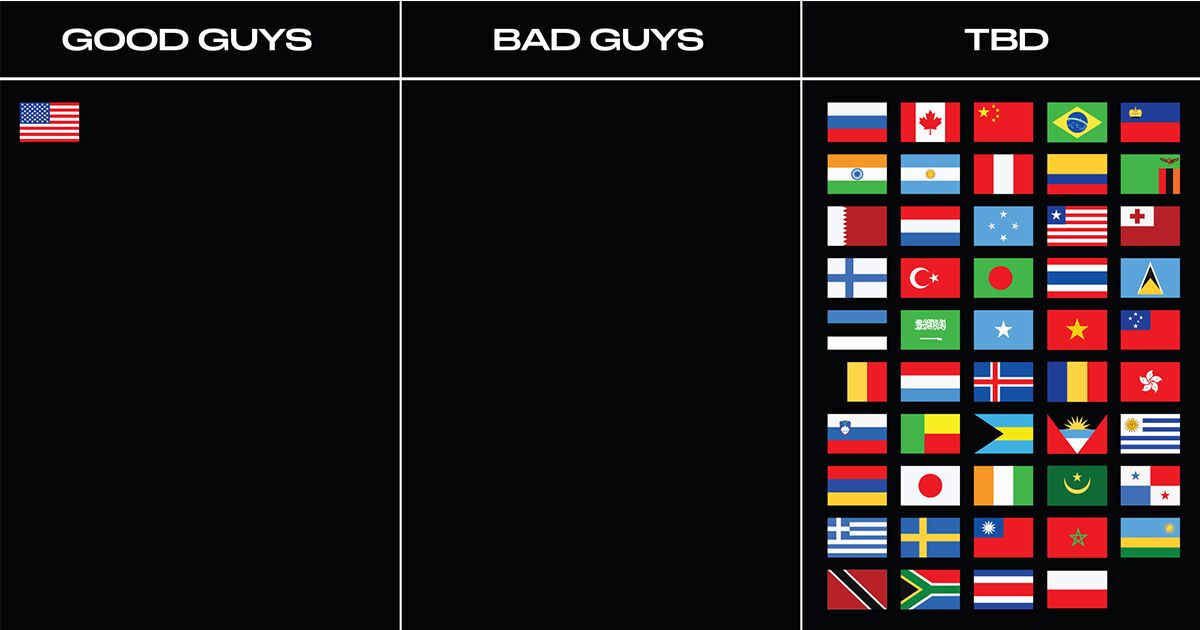

But he’s squandered whatever promise he may have had. His America First populism has devolved into a distressing comfort with autocrats such as Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, and the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte. As he demonstrated on his recent Middle East trip and at his summit with the Chinese, Trump succumbs too easily to pomp and flattery. It was good that he took the opportunity to promote the emerging Israeli-Sunni détente; it was bad that he did it at the expense of Iran, where recent elections have strengthened democratic opposition to the military-religious dictatorship. (There are now more women than mullahs in the Iranian Parliament.) His melodramatic concern about jihadi terrorism apparently stops at the border of Saudi Arabia, which has funded radical madrasas and terrorist groups throughout the region. He’s also had nice things to say about the Pakistanis, even though their intelligence services harbor and fund the Haqqani Taliban network, which was allegedly responsible for the recent massive bombing in Kabul.

His China policy is particularly strange. Unwittingly, he’s probably done as much to empower China as George W. Bush did to bolster Iran. Trump’s opposition to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which would have created a strong trading—and, implicitly, security—bulwark against China, was particularly misguided. With American markets restricted, countries such as Taiwan, Vietnam, and Myanmar will more easily succumb to Chinese economic hegemony. And Trump’s faith that China will be able to restrain North Korea’s lethal puerility remains to be proven.

In the end, the future of Trump’s foreign policy—and his administration—seems more dependent on his personality than on his staff’s attempts at coherent policymaking. His playground rants, conspiracy-mongering, and fervent disregard for recognized truths wreak havoc on international order. In general, he’s been careless in his treatment of allies and quasi-allies. His behavior will make it more difficult for the U. to persuade countries like Germany to help out if a true crisis—that is, one not of Trump’s own making—occurs. His utter lack of knowledge and subtlety (his tweeting against Qatar, which houses a huge American military base, for example) has made the world a less stable place. The world needs thoughtful, (small-c) conservative leadership—especially now, as tribal, nationalist, and sectarian rage threatens chaos not just in the Middle East and Asia but also in Europe. That sort of leadership requires vision and sagacity, of course. But it also requires grace, humility, and a certain generosity of spirit. These are not qualities Trump seems to possess. Klein, the former political columnist for Time magazine, is the author of several books, including the novel Primary Colors.

0 comments:

Post a Comment