On 26 June, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is scheduled to hold official talks with US President Donald Trump in Washington DC in what will be the first meeting between the two leaders.

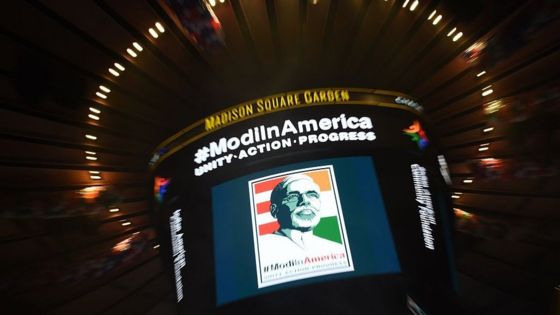

This is not the same country that witnessed roaring chants of "Modi! Modi!" at the iconic Madison Square Gardens in New York during the Indian prime minister`s first visit to the United States in September 2014.

He was then a rock star to India`s two million strong diaspora.

He is still a star to many Indians in the US and other parts of the world. But times have changed.

There is little space for global political stardom in a country led by a president whose tolerance for foreign glamour shows is about as limited as his penchant for anything international.

President Barack Obama, who met Mr Modi several times and visited India twice during his presidency, was all about the international. Mr Modi`s engagement with the Indian diaspora was not only encouraged but also cheered by officials in the White House.

The Obama years witnessed the buttressing of trade opportunities between India and the US, partly transformed the defence relationship between the two countries, and paved the way for the operationalisation of what is known as the US-India Nuclear Deal.

Further, Mr Obama made clear his unyielding aim to curb carbon emissions. On 2 October 2016, Mahatma Gandhi`s birth anniversary, India handed over an instrument of ratification to join the Paris climate change agreement.

Mr Obama`s praise was quick to come. He tweeted, "Gandhiji believed in a world worthy of our children. Modi and the Indian people," he argued, "carry on that legacy."

India`s commitment to the agreement was not only about climate change. It was about a pledge to an international system that relies on collective responsibility.

Since at least the election of President Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, the US has nudged India to work with and within this system. This was impossible for a variety of reasons, not the least because of the need to remain "free of entanglements," as India`s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru put it.

Yet, differences, when they emerged, were managed because of a common sense for each other`s vantage points.

A `promising` relationship

In the 21st Century, and ever since George W Bush was elected in 2001, the key consideration in the US-India book of relations has been future potential. For Washington`s insiders, India was the long game. The promise of Indian economic and military growth, it was surmised, would ultimately serve American interests.

A stronger India was expected to partially balance the scales with regards to China`s ever-expanding footprint. In return, India was expected to give little in the immediate term. This was about reaping dividends in the future on investments made by America in the present.

For the first time in 60-odd years, Mr Trump`s election has potentially punctured (if not ended) the underlying contours of this storyline.

Visible and quick returns are the new game in Washington.

No national leader, Mr Modi included, is likely to be spared. Take for instance Mr Trump`s scathing attack on India following the US withdrawal from the Paris agreement. Trump argued that India made its "participation contingent on receiving billions and billions and billions of dollars in foreign aid from developed countries".

The White House has also made clear its desire to reform the H-1B visa that in the past allowed thousands of Indian technology workers to make their way to Silicon Valley. Indian firms in the United States have been quick to announce their desire to hire US workers in a bid to dodge Trump`s ire.

Meanwhile, corporate America is less-than-optimistic about India`s economic progress. The Indian government`s recent decision to place price caps on certain pharmaceutical products, hence hurting profit margins for foreign firms that produce these specialised goods, is likely to be one of the many issues raised by CEO`s during a round table on 25 June.

Since taking office, Mr Modi`s government has done more to tie India`s coattails to the US political apparel than almost any other in India`s past.

This includes signing a defence logistics agreement and entering international conventions to help allow US firms the possibility of investing in India`s nuclear market.

Striking a personal bond with Mr Trump may allow Mr Modi the opportunity to explain India`s position on contentious subjects like climate change and make a case for H-1B visas.

In turn, asking for US assistance on issues seemingly close to the prime minister`s heart (such as membership to the Nuclear Suppliers Group) will require "deals" that India has been less accustomed to making in the age of promise before Mr Trump.

How Mr Modi deals with Mr Trump will partially shape the future of the US-India relationship.

Equally, it will say as much about the values he represents as a statesman who, much like Mr Obama, has promoted an international image of himself since his electoral victory in 2014.

Dr Rudra Chaudhuri is a senior lecturer in South Asian Security and Strategic Studies at King`s College, London and author of Forged in Crisis—India and the United States since 1947.

0 comments:

Post a Comment