Jaime Bermúdez has been building factories in Juárez since 1967. They do business all over the world, Nafta or no Nafta.

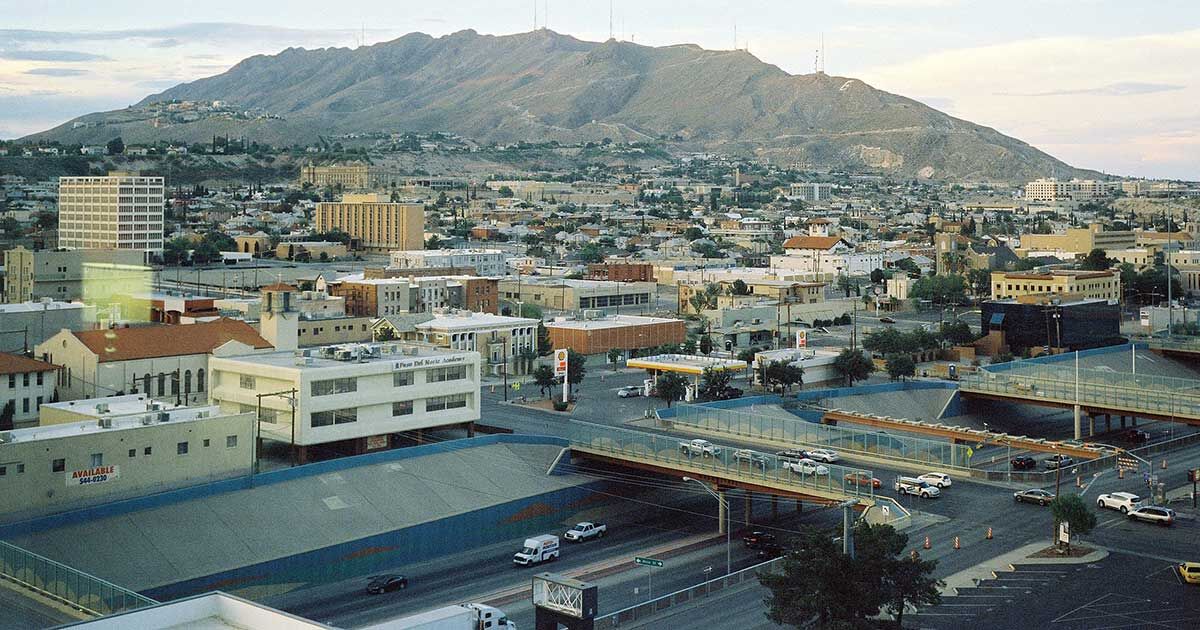

In Ciudad Juárez, along the U.-Mexico border at the foot of the Sierra Madre, a dark blue Range Rover winds through the empire built by Jaime Bermúdez Cuarón. The vehicle is carrying two of the 94-year-old real estate magnate’s sons and two of his adult grandchildren; bodyguards follow in two cars. Juárez isn’t besieged by drug cartel violence quite like it was a decade ago, but the elite are still targets. And the Bermúdezes, who’ve amassed a fortune establishing Mexico’s central role in the rise of globalization, are most definitely elite.

The caravan passes hulking factories, one after another on the creosote-and-cactus-lined streets. Each has its own concrete or iron enclosure and bears a company name on the side—Eagle Ottawa, Capcom, Copper Dots, Microcast, Filtertek—like individual fiefdoms flying their coats of arms. These are the mostly invisible weavers, processors, builders, molders, and sorters that power the global economy. They’re the brands behind the brands. The guts inside the things. These factories are churning out leather seats, light-emitting diodes, heart stents, plastic ice buckets, smartphone screens, steering shafts. Most of the pieces will be shipped on, sometimes crossing several borders and multiple plant floors, before becoming part of a finished consumer product.

That’s why these factories are known as maquiladoras—loosely, gristmills. Multinational corporations bring their raw goods to the factory like a farmer brings his grain to the mill; the factory hands it back processed and ready for the next stage of production. Almost nobody does this better than Juarenses, as the people of Juárez are known—not even, the Bermúdez family regularly emphasizes, the Chinese. “As a matter of fact, one of the prime ministers from China brought the minister of industry here and he stayed for three years,” says Jorge Eduardo Bermúdez Espinosa, the fifth of Jaime’s seven children, as the car makes its way through traffic-clogged streets. The minister later invited his father to China, says Jorge, “and he said, ‘Thanks to being in Juárez, we learned how to do it.’ ”

A gate rises as a guard waves the SUV through. It slips into a parking spot in front of BRP Inc., a Canadian manufacturer of recreational vehicles, including Ski-Doo snowmobiles, Sea-Doo watercraft, and three-wheeled motorcycles called Spyders. Here, BRP makes open-sided off-road vehicles under the Can-Am brand. The four Bermúdezes don safety glasses and fluorescent-orange vests, standing on land that five decades ago was the family cotton farm.

Loud clanking and hissing reverberate through the massive plant, which smells sharply of hot rubber. Sparks fly as an army of welders fashions the hefty frames of the vehicles, which then get moved down an assembly line of humans and robots. At the end, finished vehicles are encased in wooden boxes, loaded on semitrucks, and shipped around the world.

This is just one of about 50 maquiladoras operating inside the Antonio J. Bermúdez Industrial Park, which is named after Jaime’s politically powerful late uncle and sits on Antonio J. Bermúdez Avenue on the northeast side of town, just over a mile from the Rio Grande River. An additional three dozen industrial parks and industrial zones in Juárez contain some 400 factories of various sorts and sizes; all told, the maquiladoras employ almost 300,000 people. Dozens of other such manufacturing clusters have sprung up in Mexico, here along the border as well as deeper in the interior. But Bermúdez’s was first, in the late 1960s, and his collection of seven parks remains among the largest. “Don Jaime is the quote unquote godfather of the maquiladora sector,” says Roberto Coronado, a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and an expert on the border economy. “He was really the visionary.”

An American-educated engineer from a connected family, Bermúdez was eager to squeeze more from his cotton field in the Chihuahuan Desert. As he watched the rise of Taipei and Tokyo, he came to see potential in the growing number of unemployed workers who lived in the dusty border town, then mostly known for its brothels, gunfights, and express divorces. Bermúdez made it his mission to remake Juárez.

Today, the Bermúdez family owns a massive empire in Desarrollos Inmobiliarios Bermúdez S., whose holdings include the industrial parks, office space, concrete manufacturing businesses, and strip malls. The company is also in the middle of a raging storm over global trade. President Donald Trump has called the North American Free Trade Agreement the “worst trade deal ever made” and promised to renegotiate its terms. A round of Nafta talks, the fourth during the Trump era, began in Washington on Oct. And of course there’s the constant talk of a big, beautiful wall.

Bermúdez is, if not sanguine about all this, at ease. If he loses favor with the Americans, the Chinese are eager partners, as are the Germans, the Dutch, the Japanese. “We signed a contract yesterday for seven years,” he says, sitting in a brown leather chair in a wood-paneled den, the deep wrinkles on his face framing his piercing blue eyes. “We are very optimistic. We are making money for everybody. A wall’s not going to stop that.”

On a recent day inside Casa Bermúdez, the ornate home on the wide Avenida 16 de Septiembre that he uses as his office, Bermúdez fingers through photographs, old newspaper clippings, and contracts that document the world he built. He recalls details, mostly without hesitation. “I was so certain it was going to be successful,” he says.

The house, which is featured in more than one architectural book as a gem of Spanish colonial revival design, sits in a gritty area amid other historic buildings, some still regal in their pink, peach, and aquamarine paint. Juan Gabriel, a flamboyant Latin pop musician who died last year, lived two doors down, and fans of El Divo de Juárez continue to bring offerings to his house. On surrounding streets are storefronts marred by graffiti and boarded-up windows, testimony to the long war among the drug cartels, and between the cartels and the government.

Bermúdez comes here almost every day to work. A handsome, polished man with silver hair, he wears crisp navy slacks and a pinstriped shirt; a gold belt buckle with a cursive “B” reflects a prosperous life. His handshake is firm, and the skin on his hands silken. Over several hours and cafés con leche, it becomes clear that Bermúdez is an embodiment of the globalized world he’s helped create. He was born in Ciudad Juárez in 1923 to the Mexican landed gentry. He was educated in a fancy boarding school in Kentucky and then at Muskingum University in Ohio, where he became a civil engineer and befriended classmate John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth. He’s a prominent devotee of the sport of kings, polo, and once accompanied Queen Elizabeth II to a match between Mexico and England. He lives on a sprawling Juárez estate with three of his children and their families, who have their own well-appointed homes and share a swimming pool and private chapel.

Juárez, a city of 1.3 million, has forever been linked to El Paso, on the U. side of the Rio Grande. The trade routes plied today by rail cars and semis, passing through both cities, were traversed by pre-Columbian Indians who ferried turquoise and silver all the way to New Mexico. When the Spaniards arrived in the 16th century, they too made their way through the passage to the north. Later, the railroads, corporations, smugglers, and migrants came. “It is the most efficient overland trade route that existed then and still today,” says Patrick Schaefer, executive director of the Hunt Institute for Global Competitiveness at the University of Texas at El Paso.

For a long time, Juárez was the ugly stepchild of Mexico, its rugged hinterlands, much like Siberia is to Russia or Alaska to the U. As El Paso industrialized in the early 20th century, Juárez remained rooted in its simple cotton and copper economy. That didn’t change until Prohibition in the 1920s, when the city suddenly became a hot destination for soldiers at Fort Bliss in El Paso—and others so inclined—to come and imbibe legally. Juárez became a sort of mini-Las Vegas, with all that entails.

The Bermúdez family got into the bourbon business, forming a partnership with Mary Dowling, proprietor of Waterfill & Frazier, one of Kentucky’s leading bourbon distillers. Dowling wasn’t the sort of woman to shut down because the government passed a law. According to archives at the University of Kentucky Libraries, she stuffed thousands of bottles of bourbon into gunnysacks and hid them in the basement of her white manor house in Lawrenceburg. Then she hired family friends to help her dismantle her distillery piece by piece, load it on a rail car, and ship it to Ciudad Juárez. There she joined with Antonio Bermúdez—Jaime’s uncle—and set up the D. Distillery, for “Dowling Mexico.” The facility produced bourbon for the Mexican market, though it was probably also smuggled into the U. Antonio amassed a fortune in the whiskey business, and in 1942 became the mayor of Juárez.

With the onset of World War II, the U. government instigated the Bracero Program, an initiative designed to allow Mexican laborers to fill vacancies in American fields and railroads created by deployed soldiers. government set up stations along the border to administer smallpox vaccines and take fingerprints. Juárez became a staging area for low-skilled workers. The program ultimately lasted two decades and enlisted 5 million Mexicans.

Juárez, lacking infrastructure and jobs, stagnated. While Juarenses took their money across the border to El Paso to buy the goods and services of a modern life, Americans still went to Juárez primarily to do things they couldn’t or shouldn’t at home.

In the early 1960s the Mexican government tapped Antonio to spearhead a development program along the border not unlike the Public Works Administration in the U. during the Great Depression. The National Border Program, known as Pronaf, produced massive investment in Juárez—developers used government funds to build shopping malls and a convention center, and dot the city with tourism attractions, including an art museum and luxury hotels. Jaime, by way of his uncle, found himself in the middle of it all.

In the U., controversy was swirling around the Bracero Program. The number of ready Mexican workers outstripped the quotas, meaning more Mexicans were crossing over to work without documentation. Labor unions argued that the Bracero Program was depressing wages for American workers. In 1964, when word spread that the Lyndon Johnson administration was preparing to cancel the program, the Mexican government panicked; if more than 100,000 laborers were suddenly expelled from the U. and set up along the border, it would be a nightmare.

Jaime, along with a group of other Juárez entrepreneurs, suggested to his uncle that Pronaf hire a consultant at Arthur D. in Boston to conduct a study of the border. The firm had done a similar study for Puerto Rico that led to an industrialization plan called Operation Bootstrap. Its centerpiece was a tax structure designed to entice manufacturers from the U. mainland, notably textile companies. In October 1964 the firm issued a report recommending something similar for Mexico.

The following year, the Mexican government agreed to the consultants’ idea and produced the Border Industrialization Program. The agreement allowed U. manufacturers to set up shop south of the border and import their equipment and raw goods into Mexico free of tariffs so long as the items manufactured there were ultimately exported back to the U. This dovetailed with the recently established U. tariff item 807, which allowed for the duty-free import of U. goods that had been assembled abroad, with a tax levied only on any “value added” to the goods while they were outside the U. The provision gave U. companies an incentive to assemble their goods where the cost of labor was lowest.

Jaime now had a new mission: luring American companies to Juárez. He traveled extensively in the U., evangelizing about Juárez to anybody who would listen. American executives streamed in from the industrial Midwest, sniffing around the city to see what it was all about.

The marriage of U. tariff item 807 and Mexico’s border industrialization plan created an accelerating flow of trade. imports from Mexico under item 807 were $3. Four years later they’d mushroomed to almost $150 million, according to figures from a 1970 report by the U. Today most trade between the two countries is done under a different set of rules governed by Nafta. Last year, U. imports of goods from Mexico totaled almost $300 billion.

Bermúdez landed his first client in 1967: Acapulco Fashions, a small company that made women’s undergarments. Then a much bigger target came into view: RCA Corp., at the time the world’s largest maker of color televisions. A construction manager for the company was visiting Juárez. He quickly became Bermúdez’s honored guest.

Already, American labor unions were up in arms because of item 807. The AFL-CIO had proposed a boycott of goods imported from Mexico and was lobbying Congress to close loopholes in trade laws to discourage companies from moving south of the border. A deal with RCA didn’t come easily—the company wanted concessions that reflected its disquiet about operating in Mexico, and it demanded the project be kept quiet. But on Nov. 26, 1968, Bermúdez stood in his cotton field, with news cameras and city officials present, and placed a brick engraved with his name on a newly laid foundation that would become a 115,000-square-foot plant assembling TV parts. It was the first large-scale maquiladora in Juárez.

There’s no one spot in Juárez devoted to manufacturing. The entire town is like a factory, its streets coursing with trucks destined for the U. border or for rail spurs leading to seaports. Sidewalks are lined with little white tents flying banners that read “Vacantes”—job vacancies.

A highway that starts and ends at the U.-Mexico border curves around the city. To the south lie vast stretches of desert and cotton fields, and to the west, the Sierra Madre foothills. On the side of one of those mountains, huge white letters spell out “La Biblia es La Verdad—Leela,” or “The Bible is the Truth—Read It.”

Roadside stands hawking symbols of traditional Mexico—sombreros, hammocks, and ceramic pots—sit next to symbols of globalization: Starbucks, McDonald’s, Holiday Inn. Dental offices that offer affordable root canals and veneers to a mostly American clientele have proliferated. Trucks carrying black-clad police officers with machine guns pass regularly through the streets. The cartels are warring again.

Ownership of Juárez’s industrial parks is now international; global real estate investment trusts have been buying them up. The parks typically provide the roads, water, sewers, and other infrastructure. The Bermúdez operation does that and more: The company designs factories (Jorge Bermúdez heads the architectural practice) and builds them (it makes the cinder blocks in its own plant), then leases or sells them to manufacturers. It complements its industrial parks with nearby strip malls containing restaurants, banks, barbershops, and pharmacies.

If the industrial parks are cities inside the city, the factories are often their own little towns. At the BRP factory, which until 2006 was the RCA plant, the 1,200 workers can drop their laundry at a little kiosk when they arrive at work and pick it up washed and folded when they leave. They have access to on-site doctors and child care, and their free breakfast is served in a cafeteria overlooking a soccer field. In recent years, factories have offered recruitment bonuses because of what the industry describes as a labor shortage.

The arrival of the multinational companies and the money they bring has given rise to new businesses—lawyers, accountants, consultants. The number of educational institutions has exploded, with many companies paying for training and certifications. The number of students at the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez has jumped to almost 30,000 from 440 in 1974, according to figures from the University of Texas El Paso Border Region Modeling Project.

But the maquiladora model is still built, as it was 50 years ago, on low wages. It’s the not-at-all-secret sauce. Entry-level employees earn on average about 130 pesos per day, or about $7—and even if the company feeds you and washes your clothes and sends a bus to bring you to work, at that pay level, you’re poor. In inflation-adjusted dollars, pay is lower in many cases than in the 1970s, says Oscar Martinez, regents’ professor of history at the University of Arizona and author of the forthcoming book Ciudad Juárez: Saga of a Legendary Border City. “That has to do with the Mexican government policy of keeping the wages low in order for the country to be competitive,” he says.

As the maquiladora industry grew, it transformed Juárez from a Mexican outback with certain vices to one of the fastest-growing cities in the world. The strain of industrial development has the continuing effect of pushing Juarenses to the outskirts of town, many to the hills, where they put up shacks in desperate, dangerous areas called colonias. They’re joined there by migrants, many of them women, who come to Juárez from the interior to fill positions at the factories. Hundreds of these women have been the victims of horrible murders; the streets of Juárez are dotted with pink crosses memorializing them.

Martinez says the city is undergoing perhaps one of the most uncertain periods in its history. And that largely has to do with a man to the north.

Maquiladoras haven’t been a direct topic of the recent Nafta negotiations, but the industry is in the crosshairs of the administration, whose trade delegation argues that Mexico’s low wages and poor working conditions create unfair competition for American business. Even the slightest upward adjustment to wages in the maquiladoras or tweak in labor laws could threaten the industry’s advantages. But Juárez has strengths it lacked even a few years ago. Companies around the world are constantly prowling for lower production costs, and it’s now cheaper to hire a worker in Mexico than in China. In 2000, Chinese workers earned half of what Mexican workers did, adjusted for productivity. By 2014, Mexico’s adjusted labor costs were 9 percent lower than China’s, according to an analysis by the Boston Consulting Group.

For decades almost every maquiladora in Juárez was owned by a U. Today the figure is 63 percent. Japanese companies own 8 percent, German companies 7 percent. Other owners are from China, France, South Korea, Malaysia, Sweden, and Taiwan, according to María Teresa Delgado, president of Index Ciudad Juárez, a trade group that represents the maquiladora industry. “The Trump experience, it really opened our eyes,” she says. “At first we were all kind of nervous because we thought the world would come to an end. But there is a bright side to every dark side, and that’s what we found out. … We’re more global than we were a few years ago.”

Jorge Bermúdez calls out to his 27-year-old daughter, Alejandra, as she passes by on the back of Frijole, her brown polo pony. Like an eager coach, he runs up and down the field yelling at her as she swings her long mallet. Right here the family made whiskey. Not so many years ago, there were three other polo fields. Now there’s only this one.

The three others have factories on them, including a new one owned by Nexteer Automotive, a Michigan-based auto parts manufacturer formerly owned by General Motors Co. and recently purchased by a Chinese entity. It’s one of the family business’s first Chinese customers and supplies parts to the world’s largest automotive companies, including Ford, Chrysler, Fiat, and BMW. The factory will make steering shafts for a single customer. Production is expected to start this year. The Bermúdez family is in negotiations with a major multinational to build a factory on the fourth polo field.

“Every year my father warns me that this could be the last year that we play here,” Alejandra says. “But this year, I think that actually might be the case.

0 comments:

Post a Comment