President Donald Trump wanted to call it the Cut Cut Cut Act. Congressional Republicans settled on the less catchy and no more descriptive Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. What the legislation that began making its way through the U. House of Representatives in early November actually would do is sharply reduce taxes for business while rearranging the personal income tax with a mix of cuts and increases. House Speaker Paul Ryan called the bill “a game changer for our country.” The president said it was “the rocket fuel our economy needs to soar higher than ever before.”

That’s a lot to expect from some changes in the tax code. But then, here in the U. we’ve come to expect big things of our income taxes. On the right, cutting them has been portrayed for decades as a near-magical growth elixir. On the left, raising or rearranging them is seen as essential to making society fairer. And across the political spectrum, economic and social policies have come to rely on carving credits, deductions, and other exceptions out of the tax code to favor this or that behavior.

It can sometimes feel, in fact, as if “we have lost sight of the fact that the fundamental purpose of our tax system is to raise revenues to fund government.” That was the lament of President George W. Bush’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform in November 2005. But this bipartisan group of worthies couldn’t agree on how to raise those revenues either, instead offering two plans with differing priorities. Both were mostly ignored by Congress at the time, though some of the recommendations—such as shrinking the tax deductions for mortgage interest and state and local taxes—have found their way into this year’s bill.

Overall, though, it appears that the legislation will only make it harder to raise revenue to fund government. The House and Senate have passed budget resolutions clearing the way for $1.5 trillion in revenue losses over the next decade from the tax changes. That’s $150 billion a year to add to a federal deficit that totaled a sinister-sounding $666 billion, 3.5 percent of gross domestic product, in the just-ended fiscal year. All of which is a longer way of saying that we’ll almost certainly be back at this once again in the all-too-foreseeable future, trying to figure out a better way to fund the government.

Since 1981, the year of President Ronald Reagan’s big tax cut, Congress has passed and presidents have signed 55 bills that the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center counts as “major” tax legislation. During the prior 36 years there had been just 18. In their essential text, Taxing Ourselves: A Citizen’s Guide to the Debate Over Taxes, economists Joel Slemrod and Jon Bakija dub the years since 1981 the “modern tax policy era.” Which leads this exhausted taxpayer to wonder: What will it take to make this era end?

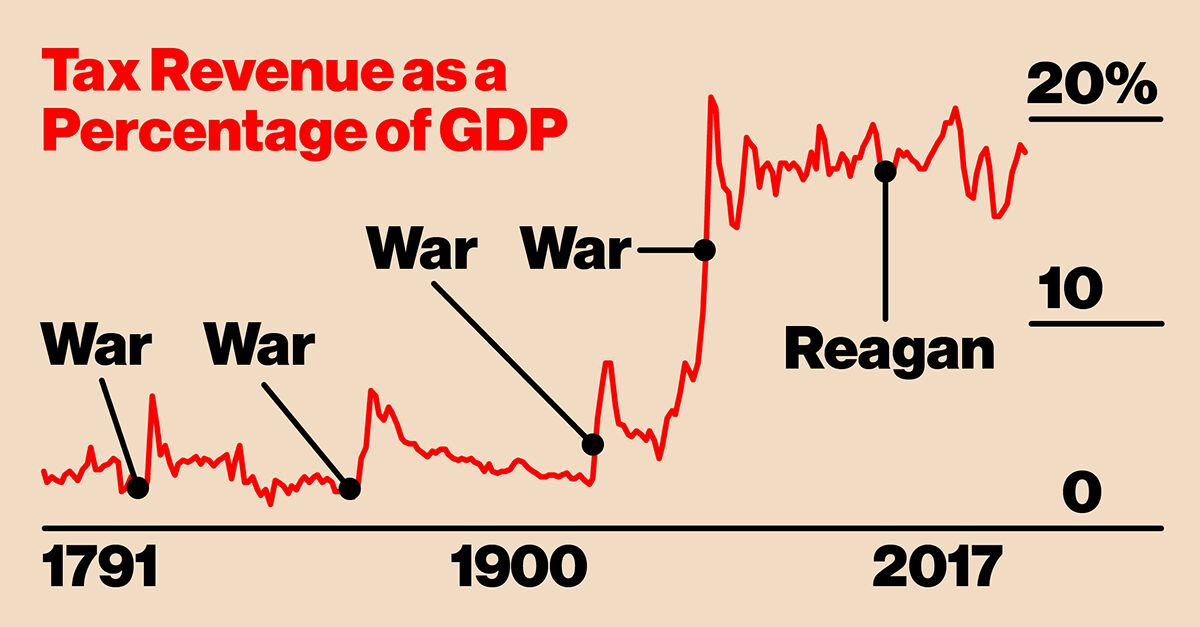

Ominously, most previous U. tax eras ended with major wars that required big increases in government revenue. Let’s hope it doesn’t take that to break us out of the cut-reform-increase-repeat loop we’re currently trapped in. But a tour of U. tax history does at least offer the hopeful message that things can change.

The no-taxes era: 1776-89. The first chapter of U. tax policy was defined by the Articles of Confederation, which left the national government to beg the states for money. Fixing this was a major priority of the Constitutional Convention of 1787. “What substitute can there be imagined,” Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist Paper No. 30, “but that of permitting the national government to raise its own revenues by the ordinary methods of taxation authorized in every well-ordered constitution of civil government?”

The tariffs era: 1789-1861. Some in the early republic had proposed that the federal government should be able only to levy external taxes, i. While the Constitution put limits on “direct” taxes—at the time understood to mean taxes on property, which became a key means of funding state and local governments—it made clear that more than just tariffs were allowed. An early foray into taxing distilled spirits sparked a rebellion, though, leaving customs duties to provide almost 90 percent of federal revenue from 1789 to the Civil War. Tariffs had the added benefit, as Hamilton argued, of encouraging domestic industry. So from the beginning, U. officials looked to tax policy to achieve economic goals beyond just funding the government. But in the tariffs era they did this in moderation, prioritizing revenue over protectionism.

The tariffs-plus-sin-taxes era: 1861-1913. The War of 1812 put a damper on trade, and thus on tariff revenue, forcing Congress to turn temporarily to excise taxes (sales taxes on specific goods, in this case mainly liquor). But it was the huge costs of the Civil War that finally ended tariffs’ dominance. To finance the war, the Union used its imagination, taxing income, estates, liquor, tobacco, playing cards, and a variety of manufactured goods. (The Confederacy struggled to collect taxes—and in the end mainly just printed money.) Most of these taxes were repealed not long after the war, but some remained to help pay the bills. It wasn’t that government had gotten all that much bigger—federal spending settled back to about the same level after the war as before, around 2 percent of gross domestic product. But customs revenue sputtered as protectionist politicians from manufacturing states pushed tariffs so high that they depressed trade. By 1913, customs duties accounted for 45 percent of federal revenue, and liquor and tobacco taxes 43 percent.

The income tax era: 1913-41. The Civil War income tax was repealed in 1872, but the clamor for a legislative answer to the explosion of economic inequality unleashed by industrialization grew in the ensuing decades. Taxes became a national obsession: A “single tax” on land proposed by the economic crusader Henry George gained a fervent following; state after state enacted inheritance taxes. In 1894, a Democratic-majority Congress imposed a tax on high earners and corporations while reducing tariffs. A year later, in a bitterly contested 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled this a violation of the Constitution’s limits on direct taxes, but the unpopularity of that ruling helped nudge the partisan struggle over taxes into a consensus.

By 1909 a Republican Congress and president, William Howard Taft, were approving a corporate income tax designed to get around the Supreme Court’s ruling and a constitutional amendment permitting a personal income tax. Four years after that, the Democrats took control of Congress and the White House and promptly imposed an income tax, a 2 percent levy on the top 2 percent of the income distribution. The military buildup for World War I brought an expansion of the tax to about 15 percent of households, with rates for higher incomes topping out at 77 percent. After the war, some Republicans wanted to supplant this progressive tax—“a modern legislative adaptation of the Communistic doctrine of Karl Marx,” one senator called it—with a national sales tax. But Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon pushed instead to keep the income tax while lowering the top rate, eventually to 24 percent. With the growth of government spending, to about 4 percent of GDP in the 1920s, and the advent of Prohibition (so long, liquor tax revenues), corporate and personal income taxes had become indispensable, with the former providing about a third of federal revenue and the latter about a quarter.

The much-bigger income tax era: 1941-81. Income tax revenue, reliant as it was on corporate profits and a narrow base of high earners, collapsed in the Great Depression, sparking a fevered search for alternatives. In 1932 a bipartisan deal for a national retail sales tax was upended by a bipartisan back-bench rebellion, with Congress opting instead for income tax hikes and excise taxes on automobiles, furs, gasoline, radios, refrigerators, and much more. (The states, meanwhile, turned to general sales taxes in a big way.) The big new spending program that was Social Security necessitated a payroll tax, which started at 1 percent of earnings in 1937. But the really big changes came with World War II, which sent federal spending’s share of GDP flying past 40 percent. Washington met the challenge by, first, borrowing lots of money and, second, making the income tax a mass tax rather than one targeted at the affluent. The number of returns filed jumped from 7.6 million in 1939 to 49.

After the war, the taxes stayed. From today’s perspective it seems remarkable that voters didn’t rebel against such a gigantic increase. Federal revenue went from an average of 4.9 percent of GDP in the 1920s and 1930s to 17 percent in the 1950s and 1960s. Vestigial wartime patriotism was key, at first. So was the 1943 shift to an ingenious, even diabolical invention: the automatic payroll deduction, which made the tax both harder to evade and less painful to pay. “It never occurred to me at the time that I was helping to develop machinery that would make possible a government that I would come to criticize severely as too large, too intrusive, too destructive of freedom,” lamented economist and conservative hero Milton Friedman, who worked on the withholding plan in the wartime Treasury Department.

It also helped that decades of strong, broadly distributed economic growth kept paychecks rising, despite the tax bite. Plus, the things government was spending money on—interstate highways, the space program, Social Security—were popular.

The cut-reform-increase-repeat feedback loop era: 1981-present. The revolt finally came three decades later. Economic growth was sputtering, conservative political ideas were resurgent, and inflation was pushing taxation beyond acceptable bounds, moving taxpayers into higher-rate brackets even when their real incomes didn’t rise. They reacted by, among other things, electing Ronald Reagan president in 1980.

While Reagan’s dislike of taxes seems to have been visceral, he had the backing of a group of “supply-side” political activists and thinkers who had coalesced in the 1970s around the notion that trimming certain taxes, mainly on high earners and businesses, would so stimulate economic growth and income that the tax cuts might pay for themselves. The Reagan cuts of 1981 in fact didn’t pay for themselves, though this was in part because Reagan insisted on cutting everybody’s taxes. Lindsey, an economist who worked for Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers and was later George W. Bush’s top economic adviser, has estimated that lowering the rate for the top bracket from 70 percent to 50 percent in 1981 did bring an increase in net revenue as top incomes grew and tax avoidance declined, and rate cuts for the next few brackets (there were 17 at the time) broke even. But most of the other 1981 provisions were revenue losers, with the indexing of all brackets to inflation likely the biggest. Overall, Lindsey concluded, economic growth and reduced tax avoidance recouped about one-third of the bill’s estimated direct cost.

Big deficits arrived in the tax bill’s wake, followed by tax hikes in 1982, 1983, and 1984. Then came the tax reform of 1986, which lowered rates and removed deductions in mostly revenue-neutral fashion—but didn’t put an end to tinkering with the tax system. Multiple rounds of income tax cuts and increases have come since. And whether or not Lindsey’s one-third estimate is exactly right, it’s nice shorthand for how Republican economists—as opposed to politicians and propagandists—have justified tax cuts to this day. They don’t claim cutting taxes increases revenue, instead arguing that bigger government distorts the economy more than smaller government, high tax rates distort more than low rates, taxes on capital (aka business) distort more than taxes on labor, and taxes on labor distort more than taxes on consumption.

Extreme versions of this thinking have motivated political proposals such as the flat tax championed in the 1990s by magazine publisher and presidential candidate Steve Forbes, among others, and the “fair tax” that radio talker Neal Boortz turned into a cause in the 2000s. The Forbes flat tax was distinguished as much by its total exemption of investment income as its 17 percent rate; the fair tax aimed to replace the income tax with a 23 percent national sales tax.

Both were reminiscent of the late-19th century intellectual ferment that led to the income tax. Back then, the discussion was driven by progressives looking to tax the rich; in recent decades it’s been conservatives aiming to roll back taxes on the rich and on business. There have been other voices in the post-1981 tax debate, of course. Liberals and some conservatives have pushed to maintain the progressivity of the tax code, technocrats have wanted to broaden the tax base, and deficit hawks have campaigned for more revenue. But they’ve mostly been fighting rearguard actions, not setting the terms of the debate.

Those rearguard actions haven’t been fruitless, though. The top income tax rate is 39.6 percent, much lower than it was in 1981, and tax rates on capital gains and dividends are much lower than that. But by the reckoning of the Congressional Budget Office, these changes haven’t made the tax code less progressive. Average federal tax rates have gone down for all income groups since 1979, but the declines have been bigger for those with low incomes than those in the top 1 percent. Yes, there are exceptions to this increase in progressivity. State and local taxes cancel out much of the effect, and other research shows that the top 0.1 percent of earners have received a big tax cut since 1979. Also, Congress has shoehorned into the tax code what are effectively spending programs, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit. But it’s still noteworthy how progressive the federal income tax remains.

Also noteworthy is how little the overall federal tax burden has changed. From 1946 through 1980, federal revenue was 17 percent of GDP. Since then it’s been 17.3 percent, on average. The mix has shifted: Corporate income taxes and excise taxes bring in a smaller share than they used to, while Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes bring in more. The share owing to personal income tax, though, hasn’t budged much. All that tax cutting, raising, reforming, and complicating since 1981 has landed us … pretty much where we started.

Federal spending, on the other hand, hasn’t stayed put. From 1946 to 1980 it averaged 18.1 percent of GDP; since then, 20. In the 1980s, defense and interest on the national debt drove spending higher, while over the past decade it’s been mainly Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The persistent gap between spending and revenue may well be the most important feature of the modern tax era. And while there have been many political discussions about reining in entitlement spending, there seems to be very little public appetite for doing so.

This unwillingness to reduce federal spending is worrisome if you think the government is inordinately large. historical standards, it is large indeed. Compared with other industrialized countries today, however, the U. spends and taxes rather modestly. Far from being the “world’s highest-taxed nation,” as President Trump has said again and again, the U. has the fifth-lowest total tax burden—federal, state, and local taxes as a share of GDP—among the 35 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the wealthy nations club.

The experience of other countries is too rarely invoked in U. In a book published in April, A Fine Mess, journalist T. Reid attempts to rectify this. His entertaining global tour shows that many of the impulses that have driven tax cutters and reformers in the U. since 1981 have also shaped tax policy elsewhere. Deductions have been eliminated, personal income tax rates have dropped, and corporate tax rates have fallen even more. statutory corporate tax rate, in fact, is now almost the highest in world, which is possibly where Trump gets his “highest-taxed nation” sound bite.

Other countries, though, have been able to enact such reforms while imposing larger overall tax burdens thanks to an extremely powerful device: the value-added tax.

The VAT, invented by a French bureaucrat in the 1950s, is a broad-based consumption tax. Instead of being levied on the final sale of a product or service, like a common sales tax, it’s imposed at every step of production, with a refund for the tax paid at the previous step. Here’s a simplified example, borrowed from an OECD primer, of how a 10 percent VAT works: A tree grower sells timber to a furniture manufacturer for $100, plus $10 in tax, and sends the $10 to the government. Then the manufacturer sells the furniture to a retailer for $350, plus a $35 tax, and sends $25 ($35 minus the $10 already paid) to the government. Then the retailer sells it to the consumer for $500, plus $50 in tax, and sends $15 ($50 minus $35) to the government. This system sounds—and is—complex, but it has the advantage of being largely self-enforcing: Each business in the production chain must report the tax the previous business in the chain was supposed to have paid to get credit for it. Because of that, and because these payments often aren’t transparent to consumers, countries are able to impose VATs at rates far higher than would be conceivable with a sales tax. Hungary has the developed world’s highest VAT, at 27 percent—which allows it to get away with a flat-rate income tax of just 15 percent—while Canada has the lowest, at 5 percent. is the only OECD member without any VAT at all.

Like any consumption tax, the VAT is inherently regressive, because poor people spend more of their income than rich people do. There are ways to offset some of that with rebates, and of course a progressive income tax can help make up for it, too. Most of the world’s other wealthy nations also rely more on government spending to combat inequality. Personal income taxes in the U. are actually both higher and more progressive than the OECD norm. But when you factor in government spending on health care and other safety net programs, most wealthy nations are much more generous to those with low incomes.

The notion that a national consumption tax in the U. could take pressure off the income tax while addressing the fiscal challenges posed by Social Security and Medicare—and maybe even allow for a bit more spending on this or that—has been batted around by would-be reformers for years. There’s even a bill currently in the Senate, sponsored by Maryland Democrat Ben Cardin, that proposes a 10 percent VAT coupled with rebates for the poor, much lower tax rates, and exempting couples who earn up to $100,000 from the income tax ($50,000 for individuals), and much lower corporate tax rates. Such initiatives have never garnered anything close to a critical mass of political support, though. That 2005 Bush tax reform panel, for example, studied both a VAT and a retail sales tax but endorsed neither.

With all this in mind, I headed out one recent afternoon to gauge the thinking of Glenn Hubbard, dean of the Columbia University Business School and seasoned veteran of Washington tax politics. Hubbard was an architect of the 2001 and 2003 Bush cuts and has warmly endorsed the new GOP tax plan. (He’s also a former Bloomberg BusinessWeek columnist.) Before I could even get the acronym VAT out my mouth, though, he launched into this mini-monologue:

“We don’t seem as a society to be willing to bring down spending as much as I would like to, and the corporate and personal income tax can’t be raised enough to cover the difference. If we’re going to have a higher level of government spending, you have to pay for it, and the most effective way to pay for it is through a tax on consumption, such as a value-added tax.”

And what about the current tax reform? Oh, it’s “still worth doing,” he said, but the U. can’t go on like this. “You can think of this as the last reform effort in this system.” The end of the cut-reform-increase-repeat era is coming.

Ah, but when will it come, and what will it take to bring it on, beyond a crisis? There was a time when federal deficits of 4 percent or 5 percent of GDP seemed like an emergency, but no longer. Politicians of both major parties have become increasingly comfortable with the chronic budget shortfalls of the post-1981 tax era, and it’s hard to blame them. The federal government has had no trouble financing its deficits (other than self-imposed trouble involving the statutory debt ceiling), and there’s a credible argument to be made that in a low-inflation, low-interest rate environment like today’s it ought to be borrowing even more to invest in wealth-creating public goods such as transportation infrastructure and basic research. Still, there’s much less of an economic argument for running up debts to pay for retirement and health care. Hubbard told me he thinks of the deficit in terms of “insurance, or fiscal space.” Without it, in case of war or economic crisis, “your capacity to intervene is reduced.” Then again, he acknowledged, “it’s not a table-banging argument to say, ‘we need fiscal space!’ ”

So no, I’m not going to bang on any tables. But someday the U. will need that fiscal space, and there’s a way to get it that would be in keeping with our history of tax experimentation and likely wouldn’t impose great economic pain. We probably should be talking about it a lot more, instead of just “Cut Cut Cut.” Justin Fox is a columnist for Bloomberg View.

0 comments:

Post a Comment